This is a story of my forever American road trip. From Connecticut to California. It is a novella of sorts.

Cross continent journeys ever since the time of Lewis and Clark have been an American indulgence. While the Europeans sailed over the seas to explore new worlds, the pioneers rode over land and river seeking a place they could call their own. Stories emerged of toil and reward, heroism and kindness. In that long tradition of an American road trip, I write about my own fortuitous journey.

My road trip has served as a reminder that what we do in the present, driven by circumstances, has the prospect of defining us. The only way for me to describe the significance of that trip is by writing about it. I write about this road trip as best my memory allows while deciphering the notes I kept during the 18 day trip, three decades ago.

“Do you know the way to San Jose,” goes to my thematic take: there are no coincidences, only serendipity.

Sally, The Lincoln Highway, by Amor Towles

The journey from Morgen to New York took twenty hours spread over the course of a day and a half.

To some that may seem like an onerous bit of driving. But I don’t believe that I’d had twenty hours of uninterrupted time to think in my entire life. And what I found myself thinking on, naturally enough I suppose, was the mystery of our will to move.

Every bit of evidence would suggest that the will to be moving is as old as mankind. Take the people in the Old Testament. They were always on the move. First, it’s Adam and Eve moving out of Eden. Then its Cain condemned to be a restless wanderer, Noah drifting on the waters of the Flood, and Moses leading the Israelites out of Egypt toward the Promised Land. Some of these figures were out of the Lord’s favor and some of them were in it, but all of them were on the move. And as far as the New Testament goes, Our Lord Jesus Christ was what they call a peripatetic—someone who’s always going from place to place—whether on foot, on the back of a donkey, or on the wings of angels.

But the proof of the will to move is hardly limited to the pages of the Good Book. Any child of ten can tell you that getting-up-and-going is topic number one in the record of man’s endeavors.

As if the endeavor to come to America 35 years ago was not enough. The staid state of Connecticut should have been idyllic to make a life in. However 1992 was proving to be different. The word recession had entered my vocabulary. Everyone seemed to be talking about this R word leading up to my graduation on May 18th, 1992. They were saying, without uttering the entire word, that R was inflicting the entire region of New England. I remember meeting a mild-mannered elected representative out of Massachusetts. Mr. Paul Tsongas told us he was running for president. Mr. Tsongas talked about the recession and how he would get rid of it within his first 100 days in the White House. I liked him for that. I also liked the gentleman who was in the White House who everyone seemed to be blaming for bringing about the recession. I liked Mr. Bush because he was saying that the recession is actually over. That was a nice thing to hear. The talk of recession sounded like an act of nature, a deluge of some sort, a plague. Mr. Tsongas, Mr. Bush, Mr. Perot and a funny gentleman, a Mr. William Jefferson Clinton from a southern state that I had never heard of, each had their approach on how to end the recession. I liked them all for it. The R thing needed to be dealt with quickly because it stood between me and a job.

Now, I could tell there was something wrong in the economy. Not because of the business degree I had just earned or the wisdom gained from Dr. Rassekh’s economics course. I could tell a recession based on one aspect and one aspect alone—there were no jobs advertised in The Hartford Courant. The Hartford Courant, long ago, had as its editor the creator of some of my favorite fictional characters—Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn. I trusted The Hartford Courant. The Hartford Courant was the oldest newspaper in America, and in New England as in the country of my birth old was considered good. The other two alternatives--The Boston Globe and its heavier counterpart The New York Times were expensive. I would have to go to the Mortensen Library to sift through the classified columns of those two expensive, big city newspapers. I felt sad for Boston and New York. These two cities were as well inflicted by the R thing. You see, there were no jobs advertised in the city papers.

I was on the look out for a job and a way forward. My friends had trickled away on their own pursuits. I had one reliable companion left. My old car. I will admit now, only now, that the vehicle was not pleasing to one’s eyes. The car was like an old haggard injured dog—with a right eye missing, but would still prop up and go the distance without a hiccup. A good loyal friend is what it was. Hard sun and snowy winters had morphed its exterior color from red to something else, a color yet to be discovered by man. The stick shift was like a chopstick twirling on noodles and the steering wheel could spin like in a toy car. Regardless, my Tercel was a loyal friend.

The Tercel would give me 40 miles per gallon when the air conditioner was switched off, and that meant I could drive aimlessly for long durations in the Connecticut countryside. Rolling hills, unannounced streams under country bridges and quaint little marketplaces. Well manicured lawns in front of homes, red brick buildings, taverns and sandwich shops across the county. As one left Farmington Avenue, the central artery of the city, past the affluent Prospect Avenue neighborhood, you would run in to large college like campuses with imposing signs on stone walls: Aetna, Cigna, The Hartford. The proud people occupying these large campuses suffered from the same plague: Recession. They had no jobs open.

In the summer of 1992, there were no jobs in Boston, no jobs in Providence, no jobs in Hartford and no jobs in the most intimidating city in the whole wide world—New York city.

So, I decided to pursue a PhD. Not because I had great ability or for that matter a subject of great inquiry that was calling out. Rather, I thought it would give me time in the familiar confines of another college till Mr. Tsongas got elected and dealt with the R word in his first 100 days. The only school I applied to—the University of Texas at Arlington sent me one of those nicely written letters that makes you want to read it over and over again for how elegantly it tells you that you have been rejected. The letter was written on heavy stationary ending with a glorious signature.

In 1992, I was too youthful for wisdom. Lack of wisdom made me excessively optimistic. You see, wisdom and optimism have that relationship I have noticed—when you have an abundance of one, you have little of other. Too much wisdom and the world looks dour. No wisdom and the world looks bountiful. I was basking in a state of no wisdom. The world looked full of possibilities. So it happened that through an acquaintance’s generosity, I was offered a job. Not in Boston. Not in Providence. Not in Hartford. Not in that most intimidating city in the whole wide world—New York city. But in a place nobody had been to. Not Ms. Carol Dalphin, our department secretary who rolled her eyes when I told her; not Dr. Tucker, the marketing professor who grimaced in a way New Englanders do when they do not like something but won’t say it aloud; not Mariellen Baxter, the portly librarian, who was physically aghast to the idea. Even the baker at South Whitney pizza looked away when I told him. Most had not heard of this place.

San Jose, California. (pronounced San + Hoh + Zay]

There were no jobs from Hartford, Connecticut to the end of the world till one got to this Spanish sounding town in California. To be precise, 2020 Charleston Road, Mountain View, California, 94043 had a job for me.

It was 1992. There was no internet. If you had a question you went to the one place that offered free information: the library. The Mortensen Library had been my retreat for two years as I perpetually lived in it, studying a bit, napping aplenty in its large cushioned sofa by the giant windows. The view outside kept changing while you idled time: the Hog river gurgling as the squirrels danced around it; and the dense trees would be dense green, then like a chameleon take on shades of orange and red, eventually shedding their leaves as everything became quiet and white. From the confines of the library, under its tall ceilings, stretched on a large cushioned sofa I would be witness to nature’s idiosyncracies. In Mortensen Library.

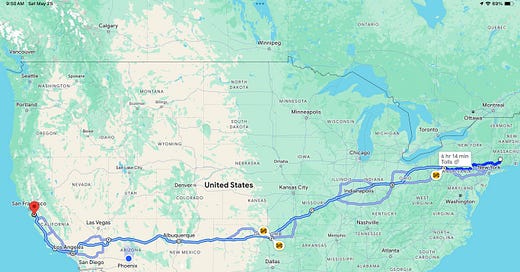

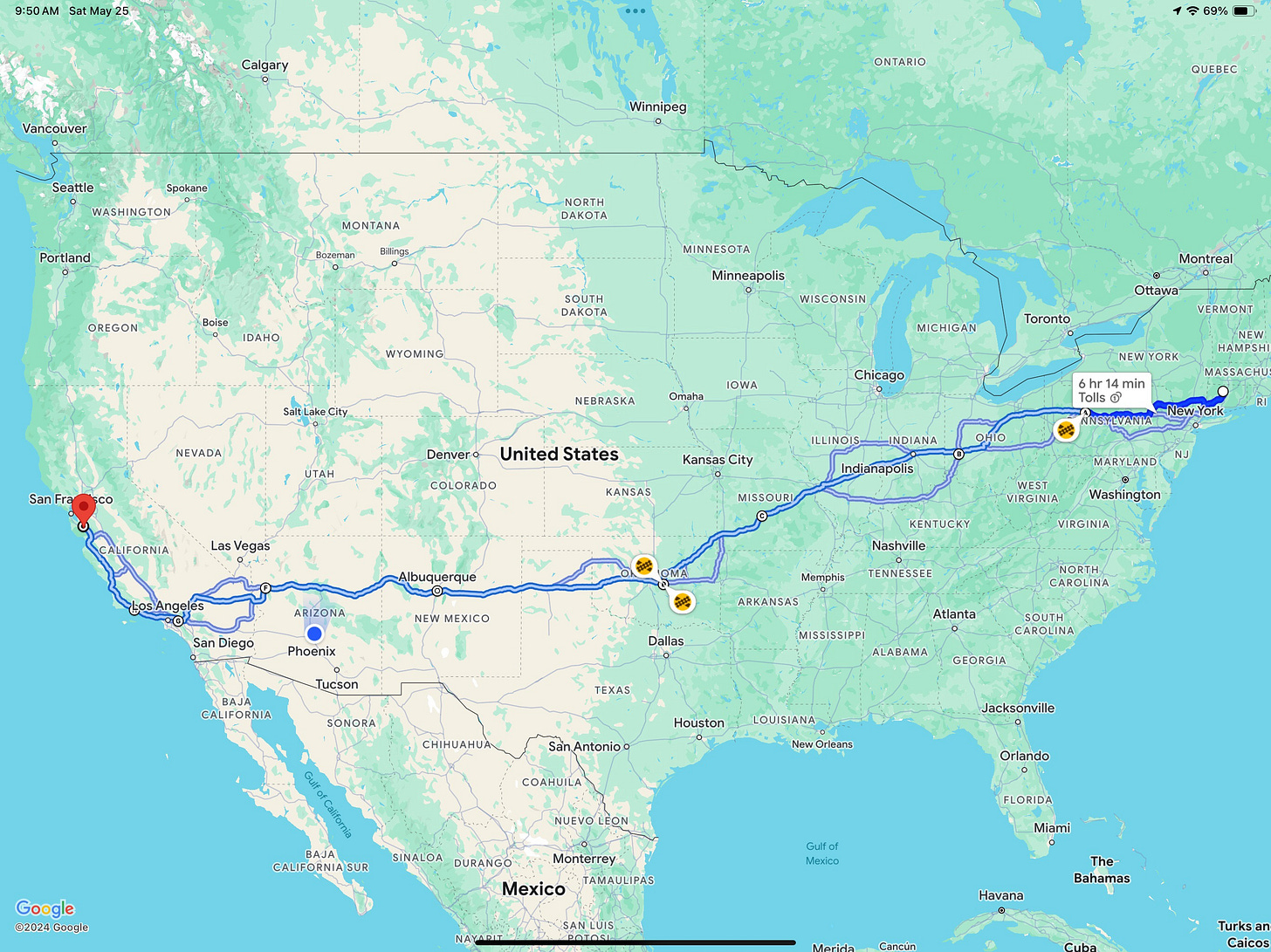

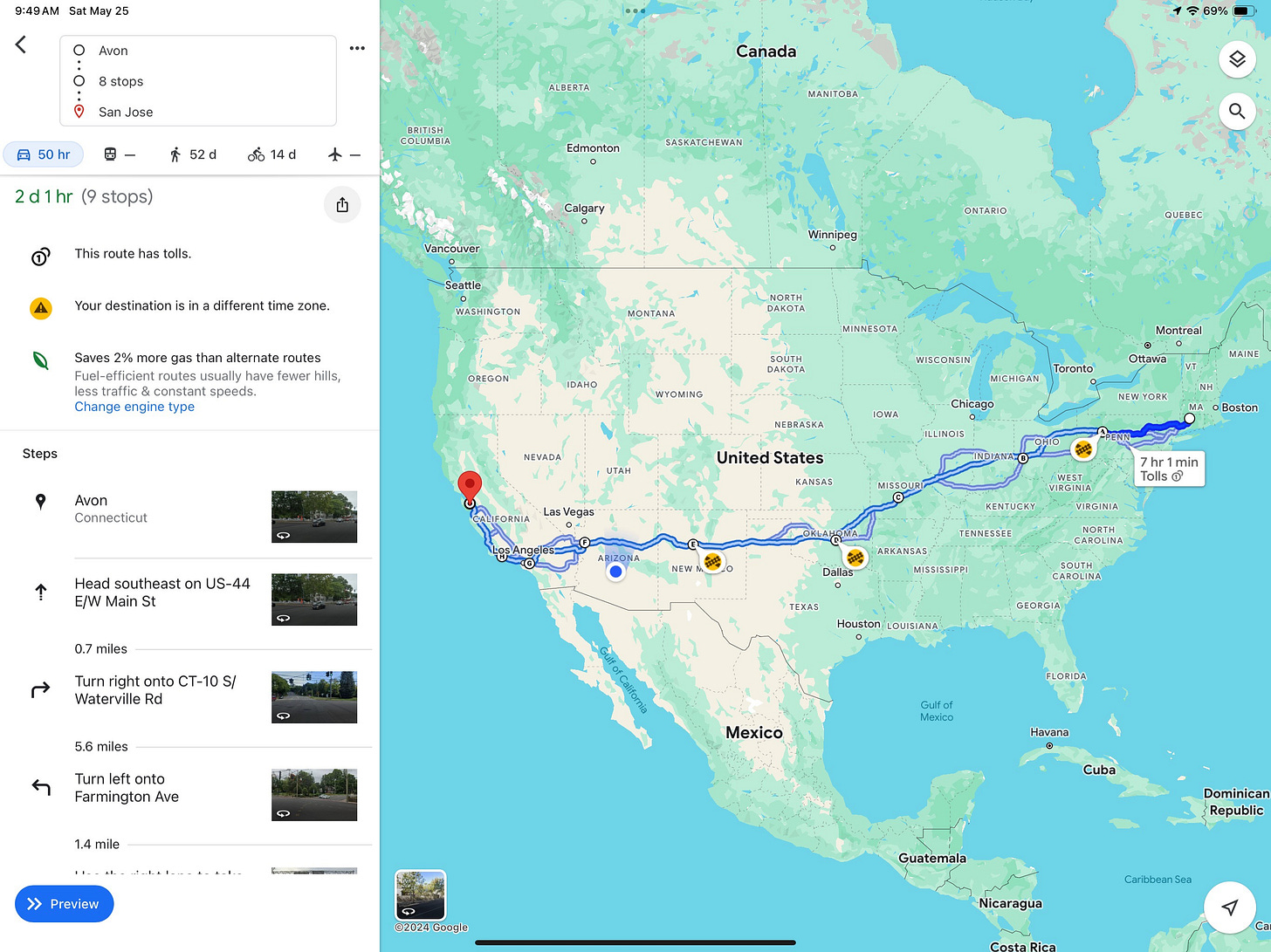

With a map of the United States sprawled open on one of those large oak tables close to the copier machine, I ran my index finger from Avon, Connecticut, my residence, all the way to San Jose, California. The northerly route and the southerly route.

By any measure, more than 3000 miles seemed a gigantic undertaking. I was not worried. Like it is written in Ithaka, I was not afraid of the long journey, even though I knew it is bound to be full of Laistrygonians, Cyclops and angry Poseidon.

At the outset, there were practical questions to be answered if I were to take this only job available to me. I had $440 in my checking account and $6000 of student debt between my two credit cards—the AT&T Universal Master card and the MBNA Visa card. Paying the minimum amount would pacify each of the credit card companies when they called about lay payments. American Express, the green elegant card had been cancelled for delayed payments. I still carried it in my wallet. You never know who would accept it, I would tell myself.

For $440 I would be able to buy a one-way airline ticket. Then there would be no money left for the weeks ahead till I got my first paycheck. I would need conveyance in San Jose and would not be able to afford a car in the early months. The prospect of flying seemed most practical. It seemed most illogical.

The drive across the continent in my 1984 Toyota Tercel with 151,653 miles on it, with one headlight, year old expired registration, no car insurance seemed like a compelling choice. The only choice. If stranded, my back-up was to abandon the car and catch a series of Greyhound bus rides to San Jose, that could be afforded based on my calculations. My brother’s nudge to take the driving route to San Jose instead of the flying route made the final call. Of course, he was not aware of certain minor details such as the expired registration, and lack of car and health insurance.

First, was a stop at Bloomfield Garage in Bloomfield, Connecticut. This is where originally, two years ago, I had bought the 1984 Toyota Tercel hatchback, 2-Dr, manual transmission, with intermittent AM/FM and a cassette player, for $1325.

I explained to Bartholomew, the mechanic, that I was one in a long succession of Lewis and Clark, undertaking the impossible, and urged him to inspect the vehicle. That I had only little money. He asked for the morning. I showed up at midday. He gave me a sincere readout—no reason, he said, the car does not make it, that the transmission and the suspension were in good shape. One can never tell with such an old car and the strain of the terrain, he added. Bartholomew was most worried about the passenger side headlight, its absence really, because driving with only one headlight poses a danger of another kind—it tends to be a magnet for the police. It was a compliance thing I assumed, that a car must have two headlights. I had a solution for that as well. I made a bet—that given the month of July for my endeavor, daylight would go past the evening. I would not have to switch on the headlight if I took a stop every evening. The cost of a night stop to avoid dealing with those good people responsible for enforcing the law.

I offered to pay Bartholomew at the Bloomfield Garage. He had changed the oil, topped the transmission fluid, filled air in the 4 bald tires and checked on the spare. He sympathetically waved my offer away. As I drove out of the establishment, I did not know then that I was to see him again in 18 years.

I had bought membership at the AAA for $55 annually. This gave me access to towing if I found myself in a situation. More importantly, AAA would create Trip-Tiks—essentially a play by play, route by route booklet customized for a road trip. Before digital navigation on devices, these Trip-Tiks were useful for their accuracy and user experience. Printed maps spiral bound with highlighted routes.

Trip-Tiks on the passenger seat, rear seat down with two suitcases and a music system with large speakers that I had bought at a thrift store on Farmington Avenue, filled my vehicle. I had chosen the southerly route given I was made aware of the Rockies and how my car would struggle on the mountain. As flat a route as possible was my ask of the helpful lady at the AAA, who called me “Sweetie.” So, it came about, I was to drive down from New England diagonally towards the south, then westwards, and then stay on one highway going west, till I got to Los Angeles—city of Palm trees, beaches and beautiful women, as well Hollywood. And then north towards San Jose. That one town in America that had a job for me.

I left Avon, Connecticut on July 5, 1992 with a plan to stretch my journey out as much as possible given my job was to start in August. Time on the road would be more affordable than living in San Jose. I had contacts along the way who I had written to on the approximate day I would be passing by. If they would be kind enough to provide room to a 22 year old.

I established a ritual each morning. I would put on my University of Hartford commencement cap, with the tassel to the right, wear shorts and no shirt. I would slide the music cassette in the chamber at the start of the day’s trip with M.S. Subbulakshmi’s “Sri Ventateswara Suprabhatham,” a prayer at the rise of dawn. Raised by a strict mother in deference to the almighty, I had reasons to offer a prayer each morning on this adventure. After that prayer concluded, I would put on another cassette to listen to one particular song and then on to the local AM/FM channels for music, incoherent talk shows and traffic information.

Somehow, the R word was not uttered when people spoke of California, where an enterprising people worked hard and made computers, planes, movies, wine all during the day and then went and played on the beach in the evening. The economy in California was always booming. Mr. Tsongas was not required in California. In photos of California, people looked happy and beautiful and fit and affluent and carefree. I was told about successful companies—Hewlett Packard, Intel, Sun Microsystems. These companies had plenty of jobs. More than there were people. Those who worked in these places had a good salary paid every two weeks from which they could afford cars with vanishing roofs, live in beautiful homes and work at leisure. They had seminars for days. Some employees traveled across the world on company money.

Adventure and Hope are lonely pursuits of the soul. In my road trip, there was to be an abundance of both. Like Willa Cather wrote in O Pioneers!

“…the long empty roads,

sullen fires of sunset,

fading, the eternal, unresponsive sky.

Against all this, Youth...”

Youth. Passers by, on to Pennsylvania, waved and honked at my youthful self. Amused by my carefree graduation attire in a peculiar vehicle. It was the summer of 1992. Anything seemed possible and worries of any kind did not register. I was spirited, bold and confident. I was looking forward to California, a land pursued by dreamers and vagabonds. I was a little of both.

My route took me from Avon, Connecticut to Dubois, Pennsylvania where there was a night stop. Throughout the journey, the plan was to start looking for hotels at about 5 pm to find the best deal. The place in Dubois offered me room and board for $17 for the night. Clean room, hospitable proprietor. I remember through Pennsylvania, there were cops everywhere—hiding underneath hoardings, on sharp curves on the highway in their Crown Victoria cars. I feared each police car as I saw them, not for any speeding violation that I was to incur—given the battered Tercel would shudder at 60 miles per hour, but for the missing right side of the car.

Next, Dayton, Ohio where I stayed at my brothers’ house, while they were away on a vacation. Barbecue every day while watching Bonanza, the western television series.

Back on the road again. As I sifted through the few channels that my FM radio would catch, I discovered songs that sounded like English versions of Hindi, Bollywood songs. The singers sang about their girl friend who had run away, leaving their mother behind, drinking excessively, getting in trouble with the law, eventually to be emancipated by the glory of the Lord himself. That was the start of a life long love for Bluegrass and country music.

The arch in St Louis was a marvel as I drove by the first time. Then the second time. And then again and again and again. The web of highways intersecting, overlapping with each other. I kept taking the wrong exit that afforded me repetitive views of the arch. St Louis, forever in my memory, is a city with a web of highways that offer you recurring views of the arch. I finally made my way out to a motel for $8 a night. In Lebanon, Missouri. In the evening, I walked in to a diner in my shorts, t-shirt and sandals. Everyone around was dressed differently. Men in jackets and suspenders, women in dresses, even children with collared shirts. I ordered a beer and the waitress said sternly that they did not serve alcohol. She said they had root beer instead, brewed in house. It sounded like a good alternative. I had a thanksgiving meal in July, in Lebanon, Missouri. Turkey, mashed potatoes, stuffing, string beans, corn bread and an apple pie with a dollop of cream and a cherry on top. While I ate, people around me took a long casual look at me. Unscathed I walked back to the hotel.

Interstate 44 took me to my next stop in Shawnee, Oklahoma, a town like the one I had grown-up in, a town that no one has heard about. I stayed for a few days at my cousin’s. Large sprawling house in a gated country club community. My nephew, a rambunctious high schooler and I were to intersect in the times ahead. One afternoon, we all went to the local Cinema and watched A League of their Own. I was once again in love with old Americana. Leaving that plush house and a neighborhood of Mercedes and Cadillacs, I got in my battered Tercel and put on the cassette tape, per the ritual, as I merged on to Interstate 40, that spans the breadth of the continent.

I was now to relax on the flat, un-elevated terrain and enjoy the landscape. There was no chance of getting lost as I was to stick to the highway where the sun sets. The ride through west Texas, towns like Amarillo named for an animal, was monotonous. Vast expanse of land on both sides. Thunderstorms so blinding that I had to pull over as my Tercel tolerated the onslaught. I stopped at ranches and often was lured in by hoardings depicting juicy steaks, Coca Cola and ice cream—for $5.99. These long rides through the vastness of America gave me quiet time and anxious excitement of what awaited. At a rest-stop, I pulled a notebook out and started writing my thoughts. On a hot summer afternoon, resting on the trunk of my car I wrote of places and people—good, kind people I had met at watering holes and gas stations. I wrote about whatever was occurring in my mind including professional pursuits, a woman for a life partner eventually but hopefully not too soon, and where I would make home. I wrote about buying a new car eventually with two headlights and zero miles on it.

New Mexico. Gorgeous. Albuquerque, not quite. In pursuit of the cheapest dwelling for the night, I found myself in a red light district surrounded by car dealerships. I left in good hurry the next morning. Back on Interstate 40 for miles, I found the Land of Enchantment enchanting. The approaching sunset wondrous. Majestic canvas overlayed my windshield with colors I had never seen before. I-40 as straight as an arrow—a hairline in the flat desert surface of the state. Stopping at a gas station, the person across filling up his tank remarked at my license plate. I wrote down what he said- “Connecticut the place actually exists.”

The New Mexico through Arizona drive left its mark. The ranches, trading posts, moccasins, colorful jewelry crafted by Native Americans, the weathered faces of people, food, cacti and free spirit in abundance, all added to the charm. People dressed like they did in Bonanza. Country music played everywhere. No sight of police cars. My fear of being stranded or being pulled over by a cop were now as long gone as the Keystone state itself. The battered Tercel did not stick out in parking lots amidst other vehicles. People spoke other languages besides English. Women were strong and well built, busy in their tasks in the outdoors. Courteous folk all around and when I asked for directions or the history of the place they took their time to explain. Food had spice, tasted good. No root beer but the real kind that made one’s head spin after a few were put away. People drank whisky and I did too, for a $1 a shot. Some nights more than a dollar was spent. I was a lone cowboy on my battered horse out to lay claim to my own land.

The cross-over to the Mojave desert was much talked about at taverns and inns. I pulled in to Kingman and stepping out that July afternoon the heat was like nothing I had experienced. I thought about the welfare of my car and let it cool down. Motel 6 at Kingman was the best inn I had stayed in the journey. Deservedly so, for $22 a night. It had a bed that one could slot a coin in that would make it shake. The bathroom sink had two small bottles—one a shampoo and the other a conditioner. Towels came in three sizes. I was tickled by the luxury of it all.

The innkeeper advised me to do the crossing of the next 100 miles as early in the morning, if not the night itself. There were to be no rest stops, no gas stations, no water or food along the way. That Kingman was abandoned latest by 5 am and there would be no cars on the 100 mile highway after 7 am as the heat melts the road itself. I was standing at the precipice of humanity, civilization itself.

This is it I thought. It is now that I shall face the Laistrygonians, Cyclops and the angry Poseidon.

I spoke to a few people at the gas station; the truckers and travelers all suggested the same—to leave before sunrise. That night, before the journey, I bought a 6-pack of beer, a large pizza and retired, tired in my room with an alarm on for 4 am. When I checked out, the innkeeper told me to stay in close proximity with other vehicles, were my car to break down. I had loaded the car up with enough drinking water that would last for days if I were to be stranded. At 430 am, I was merging on to a caravan heading west, as MS Subbulakshmi’s prayer timed the sun rise on that bright desert morning. In the company of large trucks and cars I found my community. My worries disappeared. The song from the second tape cassette was on and I started singing along. That song, I had it now memorized with the repetitive listening.

Once past Mojave, the excitement of experiencing California grew. I entered Los Angeles, and made it to an acquaintances’ home. Good rest and meal, overdue laundry. I wanted to see Hollywood. As I drove through Hollywood, accompanying me was a woman who an acquaintance of an acquaintance of an acquaintance, suggested to accompany, as I was to realize later, an attempt to set me up. There was little conversation. I was busy taking in Sunset Boulevard. Next to my battered Tercel, a long Impala with no roof pulled up. A handsome man and woman in opaque sunglasses with no smiles sat in it as Bob Marley sang.

There were two paths from Los Angeles to that one town, with a job for me--San Jose. The faster route on Interstate 5; or, the slower and scenic one, the Pacific Coast Highway. The former takes ~6 hours and is an easy drive, the latter, which I chose to take would take ~12 hours. The Pacific Coast Highway from Los Angeles to Santa Barbara to San Luis Obispo and on to Big Sur was the most beautiful thing I had ever seen. I kept stopping along the way to take in the sights. The weekday drive was not busy, although the battered Tercel stood out as glistening sports cars drove by or kept safe distance at vista points. Cool ocean air hit my face, a much needed relief from the hard desert sun I had left behind. I was starting to fall in love with California.

In proximity of San Jose, I decided to splurge and checked in to Lucia’s Lodge in Big Sur. At the precipice of a cliff it had 10 rooms and mine costed me $55 on my credit card. I figured I would pay it off once my pay check arrives. The restaurant at Lucia’s served beer, real beer, and burgers. I stayed up late till the small hours of the night lying down atop my battered Tercel. In the cold windy night, I heard the surf on the cliffs and watched the sky full of stars and falling meteors. I had managed to have company that night, by serendipity, I guess.

Behind me lay the quaint cow paths of New England and through the country, large mountains, expanse of land and desert, stretching towards the horizon. My loyal friend, my battered one-eyed Toyota Tercel had served me well. It had brought me to California without any break-downs, not even a flat tire.

Next morning I drove on to 101 to San Jose feeling immensely grateful for having experienced the country on the road. For the last time, I put the first cassette tape and then the second tape, with the song I had played each day over the last many weeks.

“Do you know the way to San Jose,” by Dionne Warwick.

Dionne Warwick, a graduate of the University of Hartford, an award winner of some kind. When I went to say a final goodbye to Julie Aldrich, the reference librarian at The Mortensen Library, she seemed excited about San Jose. She handed me a cassette and then started dancing and singing the song, gracefully. I watched her awestruck….

I’m going back to find some peace of mind in San Jose

Fame and fortune is a magnet

It can pull you far away from home

With a dream in your heart you're never alone

Put a hundred down and buy a car

In a week, maybe two, they'll make you a star

Weeks turn into years. How quick they pass

And all the stars that never were

Are parking cars and pumping gas

I've got lots of friends in San Jose

Oh, do you know the way to San Jose?

Can't wait to get back to San Jose

https://www.amortowles.com/the-lincoln-highway-about-the-book/

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/51296/ithaka-56d22eef917ec

https://www.amazon.com/Pioneers-Vintage-Classics-Willa-Cather/dp/0679743626

https://www.courant.com/2015/08/02/my-immigration-story-is-americas-story/

Great narration Girish. Surely writing is your true vocation and calling!

Awesome narration Girish. Almost felt like I was in the Tercel with you from CT to CA. You’re truly a gifted writer and orator. Did you had a camera throughout this journey ?